Politicians, both in Australia and the US, when asked how they will find the money to fund various policy proposals, often resort to the magic pudding of funding sources that is “closing the loop holes in the tax code”. After all, who can argue with stopping tax dodgers rorting the system? But as Megan McArdle recently pointed out, raising any significant revenue from closing loop holes requires denying deductions for things that a lot of middle and lower class people also benefit from. This includes, among other things, deductions for mortgage interest, employee sponsored health insurance, lower (or no) tax on money set aside for pensions and no tax on capital gains when the family house is sold.[1]

Broadly, I agree with McArdle’s point. The public, in general, are far too easily convinced by simplistic arguments about changes to taxation – as if after decades of tax policy changes there are still simple ways to increase revenues without anyone suffering. Any changes made at this point are going to cause winners and losers, and often, the people intended to be the losers (usually the rich) are less affected than some other group that also happened to be taking advantage of a particular deduction.

That said, there is one point, addressed breifly in McArdle’s article, that I thought deserved greater attention – the concessional taxation of capital gains. In the list provided in the article, it was the second most expensive tax deduction in the US at $85 billion a year[2]. You see, for a while now I have been somewhat of a closet skeptic of the need for lower tax rates on capital income (i.e. capital gains and dividends). The reason for my skepticism is two fold:

- Everyone seems to be in agreement that concessional rates for capital income are absolutely necessary, but no one seems to really understand why.

- Capital income makes up a much larger percentage of income for the wealthy than for the lower or middle class. When you hear that story about billionaire Warren Buffet paying a lower rate of tax than his secretary, it is because of the low rate of tax on capital income.

So, now that I am finally voicing my skepticism, this article is going to look at what arguments are made for lower tax rates on capital income (focusing on capital gains for individuals) and whether those arguments hold water.

Why are capital gains taxed at a lower rate?

Once you start digging, you quickly find there is a range of arguments (of variable quality) being made for why capital gains should be taxed at a lower rate. These arguments can largely be grouped into the following broad categories:

- Inflation

- Lock-In

- Double Taxation

- Capital is Mobile

- The Consumption – Savings tradeoff

Inflation

Taxing capital gains implies taxing the asset holder for any increases in the price of that asset. In an economy where inflation exists (i.e. every economy) this means you are taxing increases in the price of the asset due to inflation, as well as any increase in the value of the asset itself. Essentially, even if you had an asset which had only increased in value at the exact same rate as inflation (i.e. the asset was tradable for the same amount of goods as when you bought it), you would still have to pay capital gains tax.

The inflation argument although legitimate, is relatively easy to legislate around by allowing asset holders to adjust up the cost base of their assets by the inflation rate each year.

Lock In

‘Lock-in’ is the idea that investors, to avoid paying capital gains tax, will stop selling their assets. An investor holding onto assets to avoid tax implies they are being incentivized, through the tax system, to invest suboptimally – something economists really dislike. However, as far as ‘lock-in’ would occur, it cannot be considered anything other than an irrational reaction. Holding onto assets does not avoid tax, it only delays it, and given inflation is factored into the asset price (as discussed above), there is not even the benefit of time reducing the tax burden. The bottom line is this – to pay more capital gains tax, there must be larger capital gains. That is, even if the capital gains tax rate was 99%, an investor would still be better off making larger capital gains than smaller ones.

The other point to remember when it comes to ‘lock-in’ is that in both the US and Australia, the lower rate of capital gains tax only applies to assets held for more than a year. That means if ‘lock-in’ exists, it is already a major problem. Because asset holders can access a lower rate of tax by holding an asset for a year, they are already strongly incentivized to hold onto their underperforming assets longer than is optimal to access the concessional tax rate. In fact, increasing the long-term capital gains tax rate to the same level as the short-term rate should actually reduce lock-in by removing this incentive.

Double Taxation

The double taxation argument is a genuine concern for economists. The double tax situation arises because companies already pay tax on their profits. Taxing those profits in the hands of investors again, either as capital gains (on that company’s stock) or dividends, implies some high marginal tax rates on investment. This is one of the main reasons capital income is taxed at low rates in most countries.

Ideally, to avoid this situation, the tax code would be simplified by removing company tax altogether, as McArdle herself has argued in the past. However, we should probably both accept that, at best, the removal of corporate tax is a long way away. Nevertheless, this idea can form the basis for policies that achieve similar goals without the political issue of trying to sell the removal of corporate tax.

For dividends, for example, double taxation can be avoided by providing companies with a deduction for the value of dividends paid out to investors. Investors would then pay their full marginal tax rate on the dividends, more than replacing the lost company tax revenues.

Preventing double taxation of capital gains is a little more complicated, but the answer may lie in setting up a quarantined investment pool that companies can move profits into. Profits moved into this pool would not be subject to tax and, once in the pool, the money could only be used for certain legitimate investment activities. This would effectively remove taxation on profits going toward genuine reinvestment, as opposed to fattening bonus checks.

The overall point here is not that I have the perfect policy to avoid double taxation of company profits, but that there are other worthwhile avenues worth exploring that are not simply giving huge tax breaks to wealthy investors.

Capital is Mobile

This is one of the two arguments McArdle briefly mentions in her article. The ‘capital is mobile argument’ is the argument that if we tax wealthy investors too much, they will do a John Galt, take their money and go to another country that won’t be so “mean” to them.

When it comes to moving money offshore, obviously, not everyone is in a position to make the move. Pension funds and some investment vehicles cannot simply move country. Companies and some other investment vehicles do not receive a capital gains tax discount currently, meaning raising tax rates for capital gains for individuals would not impact them at all. Finally, even for investors that would be affected and do have the means, a hike in the capital gains rate does not automatically move all their investments below the required rate of return.

This argument also overlooks the vast array of complications in moving money offshore and the risks involved with that action. Moving assets offshore exposes investors to new risks such as exchange rate risk[3] and sovereign risk[4]. It also significantly complicates the administrative, compliance and legal burden the investor has to manage.

However, even if we concede that yes, some money would move offshore as a result of higher taxes on capital gains, let’s look at the long term picture. What is the logical end point for a world where each country employs a policy of attracting wealthy investors by lowering taxes on capital? A world where no country taxes capital!

Of course, there are alternatives. Countries (and developed countries in particular should take the lead on this) can stop chasing the money through tax policy and focus on other ways of competing for investment capital. Education, productivity, infrastructure, network effects, low administrative and compliance costs are all important factors in the assessment of how attractive a location is for investors. California, for example, is not the home of Silicon Valley because it has low taxes on capital. Pulling the ‘lower taxes to attract investment’ lever is essentially the lazy option.

Consumption vs. Savings

The second point raised by McArdle is the argument that if you reduce the returns from investing (by raising tax rates), people will substitute away from saving and investing (future consumption) and instead spend the money now (immediate consumption).

The way to think of this is not of someone cashing in all their assets and going on a spending spree because the capital gains tax rate increased. That is extremely unlikely to happen and would actually make no sense. The change will come on the margin – because the returns on investment have decreased slightly (for certain asset types), there will be slightly less incentive to save and invest. As a result, over time, less money ends up being invested and is instead consumed.

But let’s consider who would be affected. If we think about the vast majority of people, their only exposure to capital gains is through their pension fund and the property they live in, neither of which would be affected by increasing the individual capital gains tax rate. Day traders, high frequency traders and anyone holding stocks for less than a year on average would also be unaffected. Most investors in start-ups do so through investment vehicles that are, again, not subject to individual capital gains tax[5]. That leaves two main groups of investors impacted by an increase in the capital gains tax rate for individuals:

- Property investors

- High net worth individual investors

Given property investing is not what most people are thinking about when concerns about capital gains tax rates reducing investment are raised, let’s focus on high wealth investors.

The key issue when considering how these investors would be affected by an increase in the capital gains tax rate is identifying what drives them to invest in the first place. Many of them literally have more money than they could ever spend, which means their investment decisions cannot be driven by a desire for future consumption. Many of their kids will never want for anything either, so even ensuring the financial security of their kids is not an issue. The only real motivation that can be left is simply status, power and prestige. Or as the tech industry has helpfully rebadged it – ‘making the world a better place.’

If that is the motivation though, does a rise in the capital gains tax rate change that motivation?

To my mind, the answer to that question is ‘No’. These people are already consuming everything they want, or in economic parlance, their desire for goods and services has been satiated. They will gain no additional pleasure (‘utility’) from diverting savings to consumption, so there is no incentive to do so even when the gains from investing are reduced.

Of course, there are exceptions, and it is quite possible (even likely) that there are high net worth individuals who live somewhat frugally and as a result of this policy change would really start splashing out. The question is how significant is this amount of lost investment, and does the loss of that investment capital outweigh the cost to society more widely of a deduction that flows almost entirely to the wealthy.

The Research

Putting this piece together, I have studiously attempted to avoid confirmation bias.[6] Despite the fact that I would benefit personally from lower tax rates on capital gains (well, at least I would if my portfolio would increase in value for a change), I definitely want to believe that aligning capital gains tax rates with the tax rates on normal income would raise significant amounts of tax, mostly from wealthy individuals, with few negative consequences.

In my attempts to avoid confirmation bias, I have deliberately searched for articles and research papers that provide empirical evidence that lower capital gains tax rates were found to lead to higher rates of savings, investment and/or economic growth. I have not been able to find any. There were some papers that claimed to show that decreasing capital gains tax rates actually increased tax revenue, but reading the Australian section of this paper (about which I have some knowledge), it quickly became clear this conclusion had been reached using a combination of cherry picking dates[7] and leaving out important details.[8]

I did also find some papers that, through theoretical models, concluded higher taxes on capital income would cause a range of negative impacts. But the problem with papers that rely on theoretical models is that for every paper based on a theoretical model that concludes “… a capital income tax… reduces the number of entrepreneurs…” there is another paper based on a theoretical model that concludes “… higher capital income taxes lead to faster growth…”

Leaving research aside, there were a number of articles supporting the lowering or removing of capital income taxes. The problem is they all recite the same old arguments (“it will cause lock-in!”) and tend to come from a very specific type of institution. Without going too much into what type of institution, let me just list where almost all the material I located was coming from (directly or indirectly):

Even when I found an article from a less partisan source (Forbes), it turned out to be written by a senior fellow at the Cato Institute, and was rebutted by another article in the same publication.

Of course we should not ignore what people say because they work for a certain type of institution – just because they have an agenda does not mean they are wrong. In fact, it stands to reason that organizations interested in reducing taxation and limiting government would research this particular topic. The problem is that if there are genuine arguments being made, they are being lost amongst the misleading and the nonsensical.

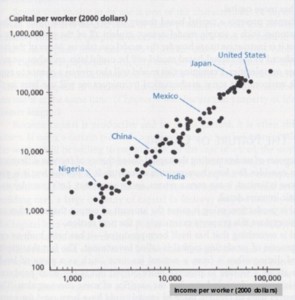

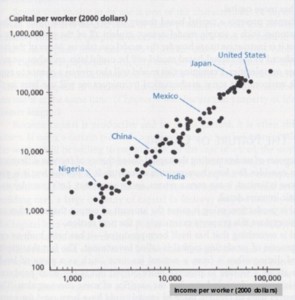

Take this argument for lower taxes on capital as an example. First there is a chart taken from this textbook:

Capital per Worker vs. Income per Worker

The article then uses this as evidence to suggest more capital equals more income for workers. As straightforward as this seems, what this conclusion misleadingly skips over is:

- income per worker is not equivalent to income for workers, and

- almost all the countries towards the top right hand corner of this chart (i.e. the rich ones) got to their highly capital intensive states despite having high taxes on capital.

A Change in Attitude?

The timing of this article seems to have conveniently coincided with the announcement by Hilary Clinton of a new policy proposal – a ‘Fair Share Surcharge’. In short, the surcharge would be a 4% tax on all income above $5 million, regardless of the source. Matt Yglesias has done a good job of outlining the details in this article if you are interested.

The interesting aspect of this policy is, given the lower rate of tax typically applied to dividends and capital gains, it is a larger percentage increase in taxes on capital income than wage income. Of course, unless something major changes, this policy is very unlikely to make it past Congress and so may simply be academic, but at least it shows one side of politics may be starting to question the idea that taxes on capital should always be lower.

The Data

Finally, I want to finish up with a few charts. The charts below show how various economic indicators changed as various changes were made to the rate of capital gains tax, historically and across countries. Please note, these charts should not be taken as conclusive evidence one way or the other. The curse of economics is the inability to know (except in rare circumstances) what would have happened if a tax rate had not been raised, or if an interest rate rise had been postponed. The same applies with changes to the capital gains tax rate. Without knowing what would have happened if the capital gains tax rate had not been changed, we cannot draw firm conclusions as to what the result of that change was.

However, what we can see is that the indicators shown below do not seem to be significantly affected by changes in the capital gains tax rate, one way or the other – the effects appear to be drowned out by larger changes in the economy. That could be considered a conclusion in itself.

Chart1 – Maximum Long Term CGT Rate vs. Personal Savings rate, US 1959 to 2014

Chart 2 – Maximum Long Term CGT Rate vs. Annual GDP Growth, US 1961 to 2014

Chart 3 – Maximum Long Term CGT Rate vs. Gross Savings, Multiple Countries, 2011-2015 Average

Gross savings are calculated as gross national income less total consumption, plus net transfers. This amount is then divided by GDP (the overall size of the economy to normalize the value across countries.

Chart 4 – Maximum Long Term CGT Rate vs. Gross Fixed Capital Formation, Multiple Countries, 2011-2015 Average

Gross fixed capital formation is money invested in assets such as land, machinery, buildings or infrastructure. For the full definition, please see here. This amount is then divided by GDP (the overall size of the economy to normalize the value across countries.

Chart 5 – Maximum Long Term CGT Rate vs. Gini Index, 2011-2015 Average

The Gini index is a measure of income inequality within a country. A Gini index of 100 represents a country in which one person receives all of the income (i.e. total inequality). An index of 0 represents total equality.

[1] Interestingly, two of these four deductions (mortgage interest and employee sponsored health insurance) will be completely foreign to Australians.

[2] A similar policy (50% tax discount for capital gains) in Australia costs around AUD$6-7 billion per year.

[3] The risk that the exchange rate changes and has an adverse impact on the value of your investments.

[4] The risk that the government of the country you are investing in will change the rules in such a way to hurt your investments.

[5] Capital Gains Tax Policy Toward Entrepreneurship, James M. Poterba, National Tax Journal, Vol. 42, No. 3, Revenue Enhancement and Other Word Games: When is it a Tax? (September, 1989), pp. 375-389

[6] Confirmation basis is the tendency of people, consciously or subconsciously, to disregard or discount evidence that disagrees with their preconceived notions while perceiving evidence that confirms those notions as more authoritative.

[7] “After Australian CGT rates for individuals were cut by 50% in 1999 revenue from individuals grew strongly and the CGT share of tax revenue nearly doubled over the subsequent nine years.” Note the carefully selected time period includes the huge run up in asset prices from 2000 to 2007 and avoids the 2008 financial crisis, which caused huge declines in CGT revenues.

[8] “Individuals enjoyed a larger discount under the 1999 reforms than superannuation funds (50% versus 33%), yet yielded a larger increase in CGT payable.” This neglects to mention that even after the discounts were applied, the rate for of capital gains tax for almost all individuals was still higher than for superannuation funds.