On occasion I get the sense from bloggers that talking about your traffic statistics is a bit like talking about salary – not something to be done amongst polite company. However, unlike discussing pay, which can generate bad feelings, jealousy, poor morale and a range of other negative side effects, discussing website stats should provide a great learning opportunity for everyone taking part. With that said, in the name of transparency, let me offer a peak under the hood here at BrettRomero.com.

Overall Traffic

For those that have not looked at web traffic statistics, first a quick introduction. When it comes to web traffic, there are two primary measures of volume – sessions and page views. A session is a continuous period of time that one user spends on a website. One session can result in multiple page views – or just the one if the user leaves after reading one article as is often the case. Chart 1 below shows the traffic to BrettRomero.com, as measured in sessions per day.

Chart 1 – All Traffic – Daily

There are a couple of large peaks worth explaining in this chart. The first peak, on 3 November 2015, was the day I discovered just how much traffic Reddit.com can generate. Posting to the TrueReddit subreddit, I posted what, to that point, had been by far my most popular article – 4 Reasons Working Long Hours is Crazy. The article quickly gained over 100 upvotes and, over the course of the day, generated well over 500 sessions. To put that in perspective, the traffic generated from that one post on Reddit in one day is greater than all traffic from LinkedIn and Twitter combined… for the entire time the blog has been online.

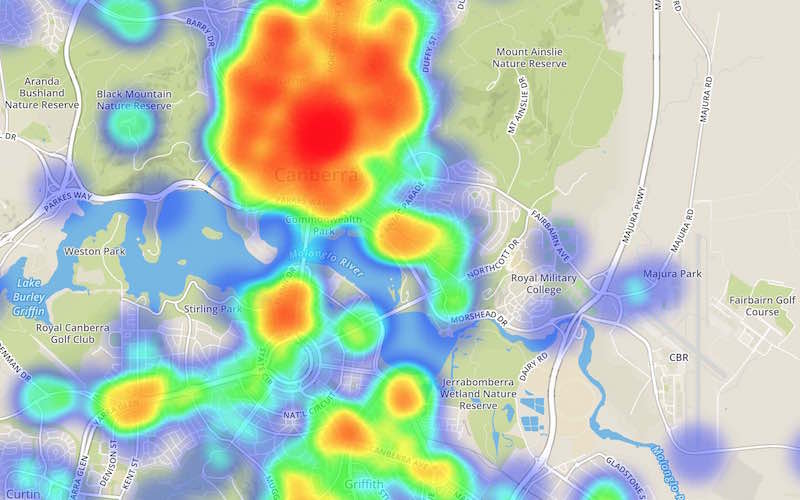

The second big peak on 29 December 2015 was also a Reddit generated spike (in fact, all four spikes post 3 November were from Reddit). In this instance it was the posting of the Traffic Accidents Involving Cyclists visualization to two subreddits – the DataIsBeautiful subreddit and the Canberra subreddit.

Aside from these large peaks though, the data as represented in Chart 1 is a bit difficult to decipher – there is too much noise on a day-to-day basis to really see what is going on. Chart 2 shows the same data at a weekly level.

Chart 2 – All Traffic – Weekly

Looking at the weekly data the broader trend seems to show two different periods for the website. The first period, from March to around August has more consistent traffic, around 200 sessions a week, but with smaller spikes. The second period, from August onwards shows less consistent traffic, around 50 sessions a week, but with much larger spikes. But how accurate is this data? Let’s break some of the statistics down.

Breakdown by Channel

When looking at web traffic using Google Analytics, there are a couple of breakdowns worth looking at. The first is the breakdown by ‘channel’ – or how users got to your website for a given session. The four channels are:

- Direct – the user typed your website URL directly into the address bar

- Referral – the user navigated to your site from another (non-social media) website by clicking on a link

- Social – the user accessed your website from a social media website (Facebook, Twitter, Reddit, LinkedIn and so on)

- Organic Search – a user searched for something in a search engine (primarily Google) and clicked on a search result to access your site.

The breakdown of sessions by channel for BrettRomero.com is shown in Table 1 below:

Table 1 – Breakdown by Channel

| Channel Grouping |

Sessions |

| Direct |

2,923 |

| Referral |

2,776 |

| Social |

2,190 |

| Organic Search |

567 |

| Total |

8,456 |

Referral Traffic

Looking at referral traffic specifically, Google Analytics allows you to view which specific sites you are getting referral traffic from. This is shown in Table 2.

Table 2 – Top Referrers

| Rank | Source |

Sessions |

| 1 | floating-share-buttons.com |

706 |

| 2 | traffic2cash.xyz |

177 |

| 3 | adf.ly |

160 |

| 4 | free-share-buttons.com |

152 |

| 5 | snip.to |

74 |

| 6 | get-free-social-traffic.com |

66 |

| 7 | www.event-tracking.com |

66 |

| 8 | claim60963697.copyrightclaims.org |

63 |

| 9 | free-social-buttons.com |

57 |

| 10 | sexyali.com |

50 |

| Total | All Referral Traffic |

2,776 |

Looking at the top 10 referrers to BrettRomero.com, the first thing you may notice is that these site addresses look a bit… fake. You would be right. What you are seeing above is a prime example of what is known as ‘referrer spam’. In order to generate traffic to their sites, some unscrupulous people use a hack that tricks Google Analytics into recording visitors to your site coming from a URL they want you to visit. In short, they are counting on you looking at this data, getting curious and trying to work out where all this traffic is coming from. Over time these fake hits can build up to significant levels.

There are ways to customize your analytics to exclude traffic from certain domains, and initially I was doing this. However, I quickly realized that this spam comes from an almost unlimited number of domains and trying to block them all is basically a waste of time.

Looking at the full list of sites that have ‘referred’ traffic to my site, I can actually only find a handful of genuine referrals. These are shown in Table 3.

Table 3 – Genuine Referrers

| Rank | Source |

Sessions |

| 17 | uberdriverdiaries.com |

35 |

| 18 | vladimiriii.github.io |

33 |

| 72 | australiancraftbeer.org.au |

3 |

| 76 | alexa.com |

2 |

| 95 | opendatakosovo.org |

1 |

| Total | Genuine Referral Traffic |

74 |

| Total | Referrer Spam |

2,702 |

What does the total traffic look like if I exclude all the referrer spam? Chart 3 below shows the updated results.

Chart 3 – All Traffic Excluding Referrals

As can be seen, a lot of the traffic in the period March through August was actually coming from referrer spam. Although May still looks to have been a strong month, April, June and July now appear to be hovering around that baseline 50 sessions a month.

Search Traffic

Search traffic is generally the key channel for website owners in the long term. Unlike traffic from social media or from referrals, it is traffic that is generated on an ongoing basis without additional effort (posting, promotion and so on) on the part of the website. As you would expect though, to get to the first page of search results for any combination of key words that is searched regularly is very difficult. In fact it is so difficult, an entire industry has developed around trying to achieve this – Search Engine Optimization or SEO.

For BrettRomero.com, search traffic has been difficult to come by for the most part. Below is a chart showing all search traffic since the website started:

Chart 4 – Search Traffic – All

Keeping in mind the y-axis in this chart is on a smaller scale than the previous charts, there doesn’t seem to be much pattern to this data. August again seemed to be a strong month, as well as the weeks in late May and early June. Recent months have been flatter, but more consistent.

Going one step further, Table 4 shows the keywords that were searched by users to access BrettRomero.com.

Table 4 – Top Search Terms

| Rank | Keyword |

Sessions |

| 1 | (not provided) |

272 |

| 2 | beat with a shovel the weak google spots addons.mozilla.org/en-us/firefox/addon/ilovevitaly/ |

47 |

| 3 | erot.co |

45 |

| 4 | непереводимая.рф |

40 |

| 5 | “why you probably don’t need a financial advisor” |

33 |

| 6 | howtostopreferralspam.eu |

32 |

| 7 | sexyali.com |

16 |

| 8 | vitaly rules google ☆*:.。.゚゚・*ヽ(^ᴗ^)丿*・゚゚.。.:*☆ ¯\_(ツ)_/¯(•ิ_•ิ)(ಠ益ಠ)(ಥ‿ಥ)(ʘ‿ʘ)ლ(ಠ_ಠლ)( ͡° ͜ʖ ͡°)ヽ(゚д゚)ノʕ•̫͡•ʔᶘ ᵒᴥᵒᶅ(=^. .^=)oo |

14 |

| 9 | http://w3javascript.com |

13 |

| 10 | ghost spam is free from the politics, we dancing like a paralytics |

11 |

Again, we see something unexpected – most of the keywords are actually URLs or nonsensical phrases (or both). As you might suspect, this is another form of spam. Other website promoters are utilizing another hack – this one tricks Google Analytics into recording a search session, with the keyword being a message or URL the promoter wants to display. Looking at the full list, the only genuine search traffic appears be the records for which keywords are not provided[1]. Chart 5 shows search traffic with the spam excluded.

Chart 5 – Search Traffic – Spam Removed

With the spam removed, we see something a little bit more positive. After essentially nothing from March through July, we see a spike in activity in August and September, before falling back to a new baseline of around 5-10 sessions per week. Although this is obviously still miniscule, it does suggest that the website is starting to show up regularly in people’s searches.

Referring back to the total sessions over time, Chart 6 shows how removing the spam search impacts our overall number of sessions chart.

Chart 6 – All Traffic Excluding Referrals and Spam Search

Social Traffic and the Reddit Effect

As was shown in Table 1, one of the two main sources of (real) traffic for the website is social media.

Social media provides a real bonus for people who are starting from zero. Most people now have large social networks they can utilize, allowing them to get their content in front of a lot of people from a very early stage. That said, there is a line and spamming your friends with content continuously is more likely to get you muted than generate additional traffic.

Publicizing content on social media can also be a frustrating experience. Competing against a never-ending flood of viral memes and mindless, auto-generated content designed specifically to generate clicks, can often feel like a lost cause. However, even though it seems like posts simply get lost amongst the tsunami of rubbish, social media is still generally a good indicator of how ‘catchy’ a given article is. Better content will almost always generate more likes/retweets/shares.

In terms of the effectiveness of each social media platform, Reddit and Facebook have proven to be the most effective for generating traffic by some margin. Table 5 shows sessions by social media source.

Table 5 – Sessions by Social Media Source

| Rank | Social Network |

Sessions |

| 1 |

999 |

|

| 2 |

868 |

|

| 3 |

224 |

|

| 4 |

69 |

|

| 5 | Blogger |

26 |

| 6 | Google+ |

3 |

| 7 |

1 |

When looking at the above data, also keep in mind, I only started posting to Reddit at the start of November, effectively giving Facebook a 7 month head start. This means Reddit is by far the most effective tool I have found to date to get traffic to the website. However, there is a catch to posting on Reddit – the audience can be brutal.

Generally on Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn, people who do not agree with your article will just ignore it. On Reddit, if people do not agree with you – or worse still, if they do not like your writing – they will comment and tell you. They will not be delicate. They will down vote your post (meaning they are actively trying to discourage other people from viewing it). Finally, just to be vindictive, they will down vote any comments you make as well. If you are planning to post on Reddit, make sure you read the rules of the subreddit (many explicitly ban people from promoting their own content) and try to contribute in ways that are not just self‑promotional.

Pages Visited

Finally, let’s look at one final breakdown for BrettRomero.com. Table 5 shows the top 10 pages viewed on BrettRomero.com.

Table 6 – 10 Most Viewed Pages

| Rank | Page |

Pageviews |

| 1 | / |

4,345 |

| 2 | /wordpress/ |

1,450 |

| 3 | /wordpress/4-reasons-working-long-hours-is-crazy/ |

1,038 |

| 4 | /cyclist-accidents-act/ |

773 |

| 5 | /wordpress/climbing-mount-delusion-the-path-from-beginner-to-expert/ |

306 |

| 6 | /wordpress/the-dark-side-of-meritocracy/ |

205 |

| 7 | /wordpress/why-australians-love-fosters-and-other-beer-related-stories/ |

194 |

| 8 | /blog.html |

192 |

| 9 | /?from=http://www.traffic2cash.xyz/ |

177 |

| 10 | /wordpress/visualizations/ |

165 |

As mentioned earlier, 4 Reasons Working Long Hours is Crazy has been by some margin my popular article. Although Reddit gave this article a boost traffic wise, it was also by some margin the best performing article I have posted to Reddit with over 100 upvotes. The next best performing, the Traffic Accidents Involving Cyclists visualization, only managed 20 upvotes.

Overall

As I mentioned at the outset, web traffic statistics tend to be a subject that is not openly discussed all that often. As a result, I have little idea how good or bad these statistics are. Given I have made minimal effort to promote my blog, generate back links (incoming links from other websites) or get my name out there by guest blogging, I suspect that these numbers are pretty unimpressive in the wider scheme of things. Certainly I am not thinking about putting up a pay wall any time soon anyway.

As unimpressive as the numbers may be though, I hope they have provided an interesting glimpse into the world of web analytics and, for those other bloggers out there, some sort of useful comparison.

Spotted something interesting that I missed? Please leave a comment!

[1] For further information on why the keywords are often not provided, this article has a good explanation.